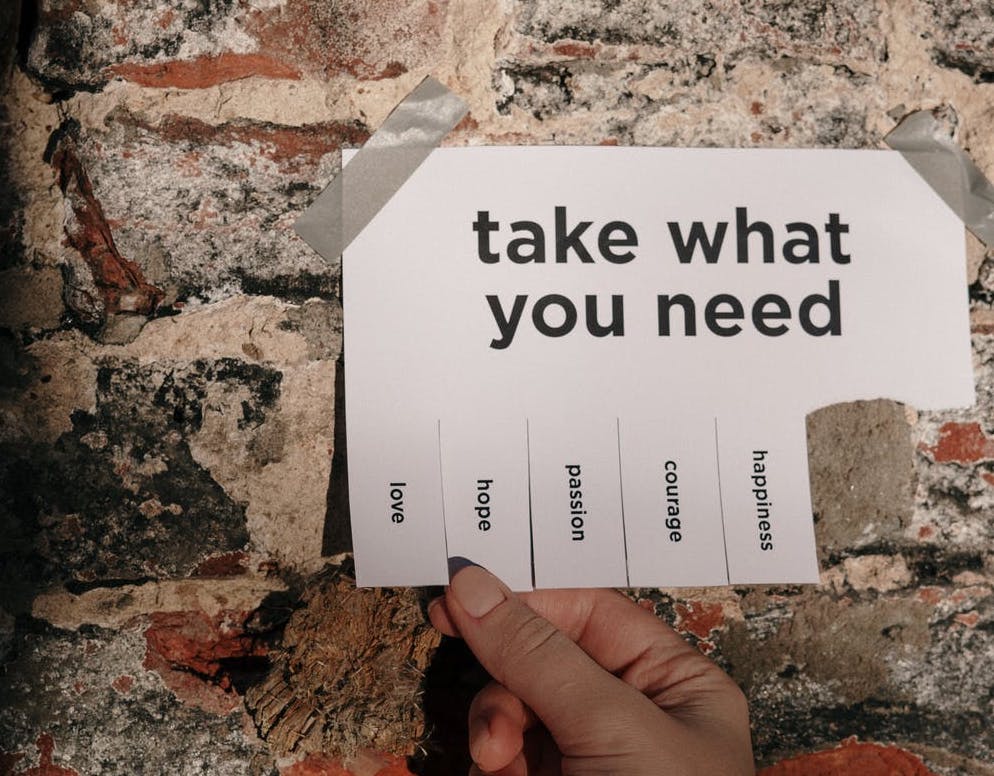

Our lives are pulled forward by a thousand tiny hopes, met or dashed. Me, I hope to sleep well tonight. I hope to see my children face-to-face, and soon. I hope one day to have grandchildren, all fit and glad. I hope the wee missus and I live long and healthy into a happy dotage, chasing each other half-naked around the house, even if on our walkers. I hope this pain in my back is from wood-hauling, not something more worrisome.

On and on it goes, pulled forward by a thousand tiny hopes, met or dashed.

None of this is wrong. It is not a failure of faith. This is the way God made us, to hope and to keep hoping. Most of what I hope for – and, I’m guessing, what you hope for – is neither selfish nor lavish. It’s modest, it’s generous, it’s generative. No one loses or suffers if any of these hopes are met. Many – not just me – win or thrive if they are.

There’s only one problem: all these hopes are so very very fragile. So utterly vulnerable. So pitiably defenseless. They are all one new variant, one old ghost, one wrong turn, one unwelcome phone call, one keen stabbing pain in the flesh or deep throbbing ache in the bones from being dashed.

They all depend on circumstances, on shaky, fickle circumstances.

I heard someone recently describe the age of Covid as the end of all hope. I think not. I think, at most, it is a sharp reminder of the fragility of hope.

Of course, Covid didn’t teach us this. It simply made painfully clear, and unavoidable, what we all already knew, and have always known, at least since we were, say, five and our beloved pet died or ran away, or twelve and our mom and dad told us they were getting divorced, or eighteen and we discovered that independence wasn’t the endless fun and freedom we had dreamed it to be, or forty-two and our spouse told us they were done with us.

Something the apostle Paul says about hope has recently caught my attention, the way a hook catches a fish. It’s in his letter to the Romans:

Hope that is seen is no hope at all. Who hopes for what they already have? But if we hope for what we do not yet have, we wait for it patiently (Ro. 8:24-25).

This is so obvious yet so easy to miss: we never hope for what we already have. I don’t hope for pizza if I’m eating it, don’t hope for love if I’m basking in it, don’t hope for solitude if I’m immersed in it. Hope awaits, and is always spent in the getting. Every hope has an expiry date – either when it’s dashed beyond recovery, or met without remainder. Then it becomes something else – dashed, it becomes grief; met, it becomes joy.

And then, either way, we start hoping all over again.

But Paul is talking here about a deeper hope. A hope that no circumstances can threaten, that is extravagant beyond asking or imagining, that only God can, and will, meet. And this: it is not spent in the getting.

He describes it this way:

For I am convinced that neither death nor life, neither angels nor demons, neither the present nor the future, nor any powers, neither height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord (Ro. 8:38-39).

A hope that is not spent in the getting. To be clear, we don’t keep hoping once we have this in full. But we never have to hope again. We will never again be pulled forward by a single hope, let alone a thousand tiny ones. We will have all we need, all we want, all we have ever hoped for, a world without end.

And so we will have reached the end of all hope.

On earth, the end of all hope is called despair. In heaven, it’s called unending unspeakable joy, day upon day upon day, though we will spend all our days in eternity trying to speak it anyhow.

Finally and forever, the life we all, deep down, are hoping for.

About